Petrostate: The Rise and Ruin of Venezuela’s Oil Giant

The Tragic Story of PDVSA and the Resource Curse That Undermined a Nation

Petrostate: El Sueño de un Petrolero

Before diving into PDVSA and how Venezuela’s political and economic history contributed to the fall of one of the world’s largest oil companies, it’s important to understand what defines a petrostate—and why Venezuela stands out among them.

A petrostate is a country whose economy heavily depends on the extraction and export of oil and gas. Thanks to vast natural reserves, these nations use oil as a primary driver of economic development. Some notable petrostates include Saudi Arabia, Iran, Chad, the United Arab Emirates, Angola, Kazakhstan, and of course, Venezuela.

Venezuela is especially significant because it holds the largest proven oil reserves in the world, surpassing even Saudi Arabia, Canada, and Iran. This positions the country as one with immense economic potential—if those resources are managed properly. But with that potential comes risk.

Petrostates are notoriously vulnerable to what economists call Dutch disease. Because these economies rely so heavily on oil exports, they are subject to extreme price volatility. A surge in oil prices can bring rapid prosperity; a downturn, if not properly managed, can lead to economic collapse. It’s a high-stakes game, and Venezuela has played it poorly.

But price volatility isn’t the only danger. In many resource-rich countries, oil booms lead to currency appreciation and a dependence on cheap imports, which hollow out other productive sectors like agriculture and manufacturing. Over time, these countries become dangerously dependent on oil. When prices fall or investment dries up, there’s little else holding the economy together.

Politically, the so-called resource curse damages governance. Oil-rich governments often rely more on export income than domestic taxation, weakening the social contract with citizens. Leaders may use oil wealth to suppress dissent, co-opt political rivals, or entrench their power. The result is a fragile economy paired with an unaccountable political system.

I call this the “gift curse”—when a country is blessed with a valuable natural resource, but due to human failure, corruption, or poor governance, that gift becomes a curse. Instead of economic prosperity, the nation inherits instability, inequality, and decline.

The Rise of an Oil Empire: PDVSA

PDVSA was born in 1976, when President Carlos Andrés Pérez nationalized Venezuela’s oil industry under the policy of La Gran Venezuela. Foreign oil companies were replaced with state-run entities like Lagoven and Maraven, forming the foundation of PDVSA. Leveraging the technical expertise inherited from multinational operators, PDVSA quickly became Latin America’s largest company and one of the world’s most profitable, with reserves growing from 18 to over 80 billion barrels within 25 years.

In the 1990s, PDVSA entered a new phase—La Apertura—which opened the industry to partnerships with foreign firms through “strategic associations.” While this brought in much-needed efficiency and investment, it came at the cost of reduced government control and tax revenue. With the rise of Hugo Chávez in 1998, the company’s direction shifted radically.

Chávez ended these liberal policies and transformed PDVSA into a tool of the state, channeling oil revenues into his social programs known as the Bolivarian Missions. Once a profit-driven and relatively independent company, PDVSA became a political instrument, losing its autonomy and drifting away from efficiency. At its peak in 1998, PDVSA produced 3.4 million barrels per day and employed 40,000 people. But the seeds of decline were already being sown.

Melting Away of Venezuela’s Crown Jewel

After Chávez took power in 1999, PDVSA's identity shifted from an efficient, globally respected oil giant to a politicized arm of the Venezuelan state. Chávez redirected the company’s profits toward his populist agenda, funding extensive social programs instead of reinvesting in infrastructure, technology, or exploration. The company’s leadership was purged of technical experts and replaced with political loyalists, weakening institutional capacity.

A turning point came in 2002 when a massive strike by PDVSA workers—protesting political interference—led to the firing of over 18,000 employees, many of whom were engineers and skilled professionals. This gutting of technical expertise severely damaged the company’s operational capabilities. As a result, production dropped, mismanagement grew, and corruption became entrenched.

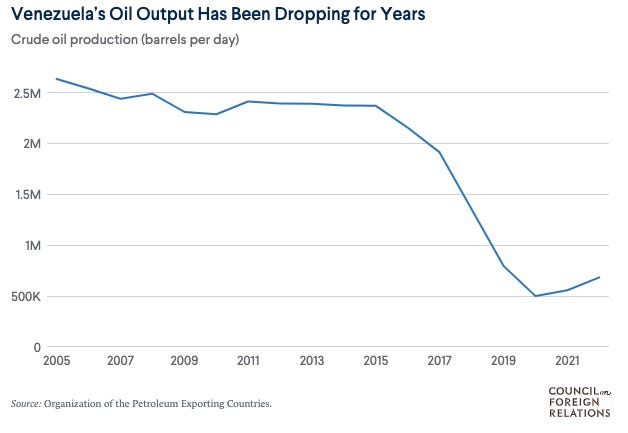

Under Nicolás Maduro, the situation worsened. With oil prices crashing and no meaningful reinvestment or reform, PDVSA’s output collapsed from over 3 million barrels per day in the late 1990s to under 700,000 by the early 2020s. International sanctions, debt defaults, and internal corruption scandals further isolated the company. Refineries crumbled, export infrastructure failed, and Venezuela—once a global oil power—began importing fuel to meet domestic needs.

PDVSA, once the crown jewel of Venezuela’s economy, became a symbol of national dysfunction — its downfall mirroring the broader collapse of the Venezuelan state.

PDVSA as a Symbol of a Failed State

The company became a microcosm of the Venezuelan economy: bloated, underperforming, corrupt. As the government used PDVSA’s revenue to paper over deficits, fund populist programs, and pay off loyalists, it became unsustainable. Reports of multi-billion-dollar corruption schemes and fuel smuggling became common. The institution that once showcased Venezuela’s economic potential now embodies its failure.

Venezuela’s Resource Curse: God’s Gift Turned to Human Folly

The fall of PDVSA cannot be separated from a broader phenomenon: the resource curse—the paradox that countries rich in natural resources often suffer from weak governance, authoritarianism, and economic instability.

Oil was Venezuela’s great fortune—yet instead of serving as a foundation for industrial growth and national development, it became the fuel for demagoguery. It allowed the government to avoid taxation, suppress dissent through subsidies, and erode democratic institutions.

As oil prices boomed in the 2000s, so did spending. But when the cycle turned, the illusion shattered. Venezuela, despite holding the largest proven oil reserves in the world, now faces fuel shortages, hyperinflation, and mass emigration.

“Oil was God’s gift to Venezuela, but in human hands, it became a curse.”

The Giant Brought to Its Knees

Today, PDVSA exists more as a relic than a functioning oil company—a hollowed-out institution caught between its past glory and present decay. The numbers are damning, but they only tell part of the story.

A Collapse in Output

At its peak in the late 1990s, PDVSA produced 3.4 million barrels of oil per day. Today, that figure has plunged below 800,000. Refineries sit idle, pipelines corrode, and oil fields lie dormant. Years of neglect, brain drain, and systemic dysfunction have left the company barely able to meet domestic demand—let alone compete globally.

A Legacy of Corruption and Isolation

PDVSA has become synonymous with corruption. Billions of dollars have vanished through kickback schemes, phantom contracts, and illicit fuel smuggling. Sanctions imposed by the U.S. and European Union—though aimed at pressuring political reform—have further isolated the company from financial markets and technological support. The result is a paralyzed operator with no clear path forward.

The Bitter Irony of Fuel Shortages

Despite sitting atop the world’s largest proven oil reserves, Venezuela now struggles to keep its gas stations supplied. The domestic refining network has all but collapsed. The country that once fueled the region must now import gasoline—highlighting the tragic irony of a nation rich in oil but poor in energy.

Broken Alliances and Shattered Trust

Foreign partners once saw opportunity in Venezuela’s oil fields. But Chevron, Rosneft, CNPC, and others have scaled back or withdrawn entirely, deterred by opaque governance, legal uncertainty, and operational chaos. Investment has dried up. What remains is a company cut off from the world—and from the future it once promised.

Repair of Broken Glass

The fall of PDVSA is not just the story of a failed company—it’s the story of a nation that shattered its most valuable asset. Venezuela had the reserves, the talent, and the infrastructure to lead the world in energy production. What it lacked was the discipline, governance, and vision to sustain it.

Now, PDVSA stands as a broken giant, and Venezuela faces the slow, painful work of repair. Like fractured glass, rebuilding trust, capacity, and credibility will require precision, patience, and resilience. It won’t be enough for oil prices to rise again. What’s needed is structural reform: depoliticization of the oil sector, reinvestment in infrastructure, and a return to institutional integrity.

For now, the world watches. Investors remain hesitant, foreign partners stay distant, and the Venezuelan people continue to pay the price for decades of mismanagement. Yet in every collapse lies the potential for rebirth.

“Repair of Broken Glass” is possible—but only if Venezuela chooses to see oil not as a political weapon, but as a national responsibility.

To the People of Venezuela

And to the Venezuelan people—

The oil beneath your feet is not a curse, nor a weapon, nor the possession of any regime. It is a gift of the earth, and it belongs to the people—for the people.

Yes, it has been misused. Yes, leaders have distorted its purpose, squandering its promise and calling it progress. But resources do not fail—people do. And in that failure lies a choice.

The future of Venezuela will not be decided by oil alone, but by how its citizens choose to steward it. The ground holds wealth, but the true power lies above it: in your capacity to demand better, to build stronger institutions, and to reimagine a state not defined by dependency, but by opportunity.

History has offered a painful lesson. But with it comes clarity. What was once a curse through human error can be reclaimed as a blessing through human will.

The rise of Venezuela need not be a dream deferred. The nation can rise again—and this time, not just on what is in the ground, but on what is in the hands and hearts of its people.

Al Pueblo de Venezuela

Y al pueblo venezolano—

El petróleo bajo sus pies no es una maldición, ni un arma, ni propiedad de ningún régimen. Es un regalo de la tierra, y le pertenece al pueblo—para el pueblo.

Sí, ha sido mal usado. Sí, los líderes han distorsionado su propósito, desperdiciando su promesa y llamándolo progreso. Pero los recursos no fallan—fallan los seres humanos. Y en ese fracaso yace una elección.

El futuro de Venezuela no lo decidirá solo el petróleo, sino la forma en que sus ciudadanos elijan administrarlo. La tierra guarda riqueza, pero el verdadero poder está arriba: en su capacidad de exigir algo mejor, de construir instituciones más fuertes, y de imaginar un país no definido por la dependencia, sino por la oportunidad.

La historia ha dejado una lección dolorosa. Pero también ha traído claridad. Lo que una vez fue una maldición por error humano, puede recuperarse como bendición por voluntad humana.

El resurgir de Venezuela no tiene por qué ser un sueño aplazado. La nación puede levantarse de nuevo—y esta vez, no solo por lo que hay bajo tierra, sino por lo que hay en las manos y los corazones de su gente.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2024, April 19). Venezuela: The Rise and Fall of a Petrostate. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/venezuela-crisis

Rapier, R. (2019, January 29). Charting the decline of Venezuela’s oil industry. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rrapier/2019/01/29/charting-the-decline-of-venezuelas-oil-industry/

OpenAI. (2025, May 18). Response from ChatGPT to a query about citing sources related to Venezuela's oil industry decline [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat